Nothing Is Too Small for a Revolution: Anarchist Films by Nick Macdonald

Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E. 60th St.

Friday, December 2, 2016 at 7pm

Q&A with Nick Macdonald and critic Jonathan Rosenbaum

Presented by South Side Projections, the Logan Center for the Arts, and the Chicago Underground Film Festival

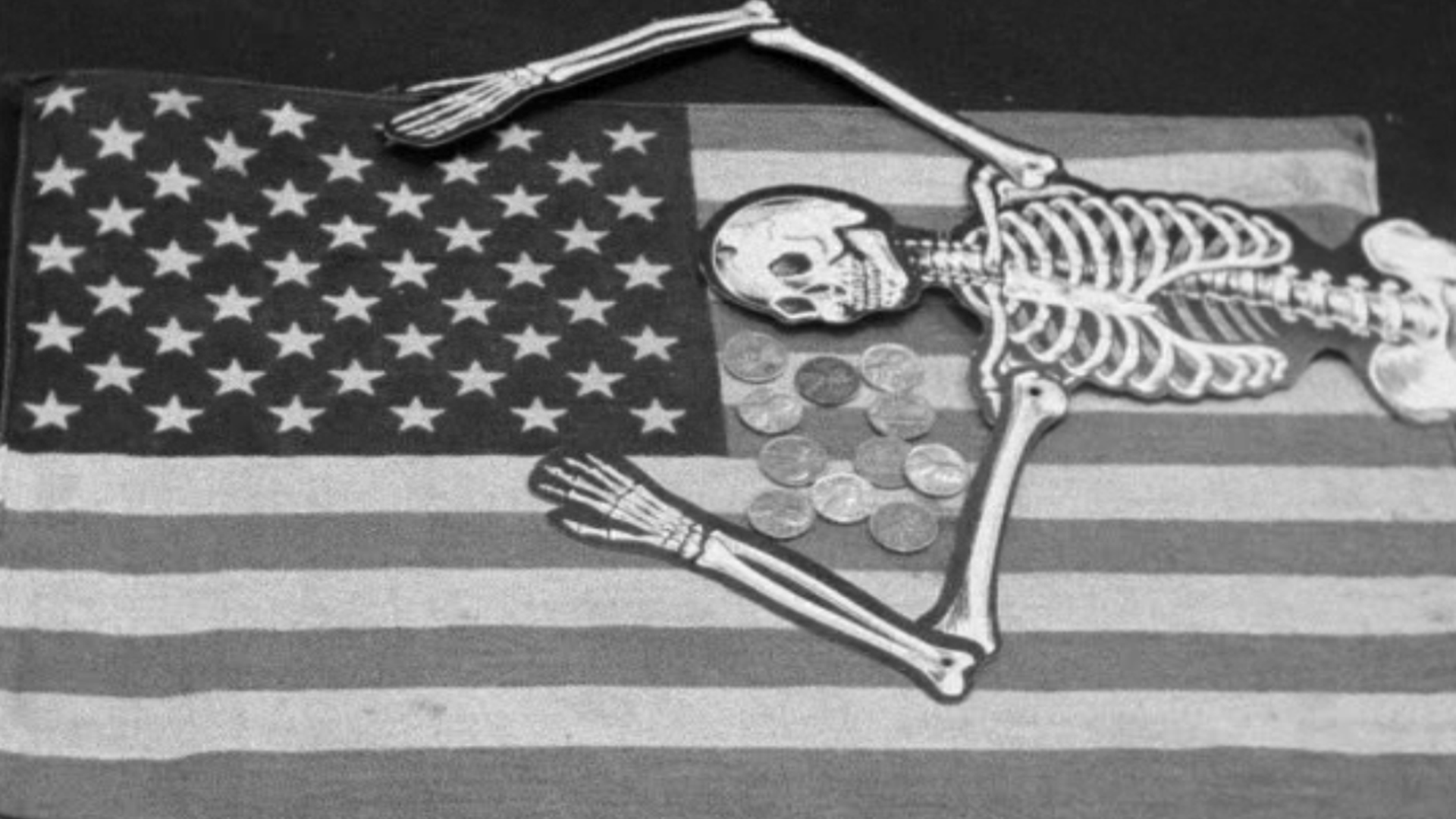

In the early to mid 1970s, Nick Macdonald made several political essay films in and around his New York apartment. Influenced by anarchism, the films are unique, personal projects that eschew traditional documentary footage in favor of a sort of bricolage technique in which Macdonald used narration, newspaper cutouts, knickknacks, photographs, guerrilla skits, and wordplay on a letter board to explore such topics as the Vietnam War, Palestine, the Attica uprising, women’s liberation, and the antiwar movement. Never before shown in Chicago, these films are not historical artifacts but surprisingly relevant object lessons in using personal art to address current political issues. All films will be screened from Macdonald’s own 16mm prints. Chicago-based film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum will moderate a discussion with Macdonald after the screening.

Break Out! (1970, 25 min.) is “a self-criticism, self-analysis” in which Macdonald struggles with his own status as a self-declared “armchair radical.” Wondering what real effect making films and attending demonstrations can have, he wrestles with the idea of violence and examines his own excuses (protecting his family, protecting his life) for not “being radical as opposed to talking radical.” In a section that introduces the letter board and bricolage technique that would become so prominent in his filmography, he lays out a radical 12-point program for the attainment of a more decent society; a coda proposes a halfway point between armchair radicalism and bomb-throwing.

Macdonald lays out his theory of anarchy—in its purest sense of a rejection of hierarchy—in the seriocomic No More Leadershit (1971, 4 min.), which argues that protesters, police, and soldiers alike are not the perpetrators of violence but its victims at the hands of leaders—even the ones you agree with.

Macdonald’s magnum opus—or at least the film that’s been written about the most—is The Liberal War (1972, 33 min.), staged as an attempt to explain the Vietnam War to members of a future anarchist society. Along with a voiceover that emphasizes that this story is just “my own view, the way I see it” and visual wordplay on a letter board, Macdonald’s bricolage technique uses odds and ends lying around his apartment to literalize the metaphors of invasion and occupation: the puppet government of South Vietnam is a sock puppet with Ngo Dihn Diem’s face glued onto it; dominoes and then plastic army men are set up and knocked over on a map of Vietnam; Macdonald’s own Harvard diploma is cut into paper dolls to illustrated the prevalence of the war’s architects at that esteemed institution. The film rejects the widely held belief that the war came about through a series of accidents and well-intentioned but misguided decisions by the “best and brightest,” arguing instead that it was the necessary outcome of American exceptionalism.

The screening concludes with a pair of films about women’s liberation, in which Macdonald explores what this anti-hierarchical philosophy looks like in interpersonal relationships. Concluding that “nothing is too small for a revolution” in Our Common Senses (1976, 6 min.) and Acts of Revolution (1976, 6 min.), he proposes that simple things like listening, reading to one’s children, and crying can be revolutionary acts.

Bios:

After making three silent comedies in college, and a documentary about refugees from the Spanish Civil War, Nick Macdonald made seven political (essay) films from 1970 to 1976. These films have been shown at Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Academy of Music, and various university and leftist forums. He also filmed two short color movies on Cape Cod. Made on extremely low budgets with a homemade quality to them, his films don’t rely on documentary footage but, instead, use photographs and guerrilla skits, often taking place within his apartment. Macdonald’s book, In Search of La Grande Illusion, on Jean Renoir’s classic film, was published in 2014 by McFarland & Co. In 2015, MoMA accepted his films for their archives and they are currently being processed by the museum.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, born in Alabama in 1943, was the principal film critic at the Chicago Reader from 1987 until 2008. He maintains a web site archiving most of his writing at jonathanrosenbaum.net.