Welcome to This House: Q&A with Barbara Hammer

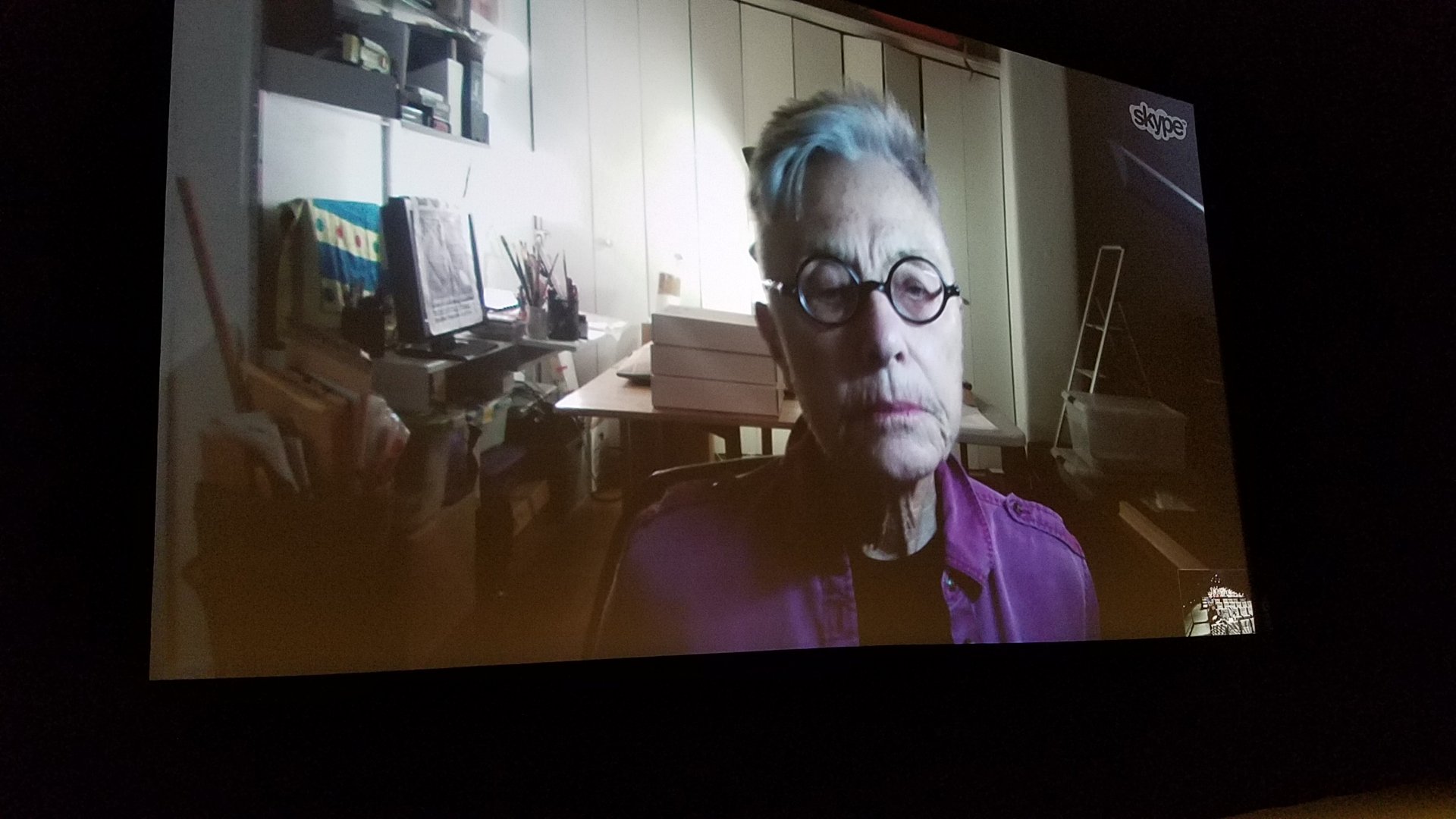

Skype introduction/Q&A with experimental filmmaker Barbara Hammer before our February 17, 2018 screening of Welcome to This House at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, moderated by University of Chicago professor Jennifer Wild. The event was co-sponsored by the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts and the Nightingale Cinema, part of a two-night mini-retrospective of Hammer’s work.

Michael W. Phillips Jr. (MP): I was wondering if you could start by just giving a brief overview of how you decided to make this film.

Barbara Hammer (BH): Yeah, I was thinking about that. I actually was in London, having a retrospective at the Tate Modern, and I saw a residency in Cape Cod, and I thought, “Oh, I’d like to go to Cape Cod.” And so I wrote a grant proposal that I would study the landscape and compare a modernist home, because there are quite a few of those from the seventies there, with a dune shack that I’ve lived in. Then I thought the grant was missing a human figure, and we won’t have a sense of geography without that. And my friend John David Rhodes said, “Wasn’t Bishop on the Cape?” And so I did a little research and right away, there she was at Wellfleet. She went to a girls’ sailing camp in Wellfleet and had lived there every summer when she was going to Vassar. And this was perfect, because I was able to get the grant, live in a modernist house, and begin to shoot a sample of what the Bishop film might look like. And little did I know that the Guggenheim – that funded the film – that they’re wild about Bishop. And about two different people got projects about Bishop the year I did, and Edward Hirsch – who’s a poet, and who’s the president of the Guggenheim – had all the Bishop books behind his desk when I went in. So I struck a gold mine, is really what it is, because I had applied for a Guggenheim for about ten years, fifteen years in a row, and no explanation, but I never got it. So that was how the film began. In a lot of ways by happenstance.

MP: How did you decide to pursue it to the extent you did? What was it about Bishop, or maybe the interaction of Bishop and architecture, that made you decide to follow it through to Brazil?

BH: Well, I met a professor emeritus at Vassar and she was an expert on Bishop, and I interviewed her. We went for lunch. I took notes, and I didn’t know these names she was mentioning. “Ouro Preto.” I was just scribbling. And it was such a complex life – Bishop’s was – that I thought, “This is really interesting.” And I’ve been interested in, you know, the closet, in terms of fifties modernism. My films with Hannah Höch, and Alice Austen – she’s earlier – Claude Cahun, and Marcel Moore, all relate in one way to a different time period, when lesbians were in the closet. And so I was concerned about Bishop in that much of her poetry wasn’t personal, or you had to dig to find her speaking with an “I” voice, let’s say. And so I just thought that maybe the homes that she lived in would influence the way she wrote, and of course the home is in a location. So I went to Key West, and several locations in Brazil, and Cambridge, and investigated. And the film became a person in relationship to architecture, maybe because I used dramatic reenactment to try to show a physical body within these spaces, rather than just a photograph. It seemed to me that you wouldn’t get a sense of scope unless you did that. It was a hard film to make. A lot of research. And exciting.

Jennifer Wild (JW): Hi, thank you so much for being here with us. It’s a great honor. So I just wanted to ask a quick question, it might sound – following your work for a long time, there’s such an investment in history. And one of the most well-known aspects of your work is the queer history trilogy, where you work on autobiography, you work on a kind of queering of history in general, with history lessons. There’s this idea in your work, as you’ve already mentioned, of kind of bringing forward invisible histories. And I’m curious about how – insofar as you really conceive of your work as always having social practice inside of it – I’m curious about how you might talk about this commitment to history, and making history, even if it’s history that is rewriting some histories. And just maybe let us hear you think about that. And how do you conceive of this film, too, as having a social practice element in terms of its history and its engagement with history?

BH: Well, when I was a student at San Fransisco State, not only did we not see any lesbian films, but we only say one film by a woman. That was Maya Deren. I found out later that she was bisexual, through some, again, deep research that I had to do. So it’s very concerned, because I came out in 1970, that there wasn’t a platform to stand on. There wasn’t a visible history. And that really led to the early films of physical expression, through lovemaking and satire in Menses and Superdyke. And then later I engaged my mind as well, and then we go to the trilogy that you mentioned, where it was more exciting maybe with maturity to open up questions of history. I was reading Benjamin, who says that we know history through fragmentation, and that’s exactly what I had found, tiny little scraps of evidence. You know, The New York Times did not print the word lesbian until 1920. And the fact that I hadn’t heard the word until I was thirty. I came out when I was thirty. So, I mean, it’s a totally different landscape today than it was then. But that was my impetus.

I didn’t know what I would find with Bishop. I found that she was out to her friends, and that wasn’t a secret. And she had a good many friends, I would say, in artistic circles. Less casual friends in terms of the working people of Brazil. And, you know, part of it is conjecture, but also to see these homes, they were quite isolated. And even though she said, “I always had to live by the coast,” she was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, and grew up in Canada, outside of Halifax in Great Village. There’s a large river there. It was still maybe a safe place for a lesbian to be. You know, like Willa Cather. Willa wanted to be known for her work, you know? And I understand that. I want to be known for my work. Yes, I’m a lesbian, and yes, I am an artist. But this typecasting, and – I mean, identity politics goes so far. And then you want to have the whole rounded person there, represented. And I just didn’t know whether Bishop would like what I was doing or not. But it didn’t matter. It was time. And in a biography, if you’ve read – Megan Marshall’s biography has come out since. And then the work of Robert Lowell, and their relationship was quite intense. We all approach things maybe from the generation in which we live. And somebody will maybe come into my work, fifty years from now, and try to find out why some things are missing, they may think. I don’t know. It’s up to us to scratch and dig and shuffle and reconfigure, because by doing that we get a new possibility of meaning, and we’re not stuck to an early biography, or even Megan’s recent biography. We’re freed by letting disjunctive ideas come together, which would then open up a new space. And that new space can be a queer space.

So queering Bishop in Brazil wasn’t so easy. Many people are kind of – well, they’re not kind of. They are committed and dedicated to the idea that she was a poet, and that was all. And that’s what we need to know about her. And a Catholic society, a society that just recently closed a queer exhibition in São Paulo this last month. I had a retrospective there, I think it was a year ago now, in the summer. And that went fine, but there has been a change of government since then, and more scandal. So it’s difficult for the people of Brazil, I think. I don’t know, I’ve sort of talked all over.

JW: No, it’s a great answer. I mean, bringing these two things together, bringing fragments together in that Benjaminian sense is something I sense in your work. And one of those things is bringing materiality. And I’m thinking here of one of your more recent films, Maya Deren’s Sink. Also a film about a woman that you’ve mentioned already. This object, this very domestic, material object. And then, of course, the discourses on the body and corporeality. You seem to have in your history-making a really specific relationship to material things.

BH: I think so, I do. And to film itself, before we had digital files. So that I would scratch, and touch it, and we would know that this was an object that we were seeing projected on the screen. It wasn’t living in X’s and zeros in cyberspace. So moving into the digital world, it’s much less material, is it not? And so meeting you, and the audience, is the materiality, then, in my practice today. And I’m really sad I can’t be there, because I just love interacting with an audience, and I would be behind Michael in that second group back there of folks, asking you all questions. Hi! Yes, that’s where I’d be. Hi! I see some white hairs there. (Laughter) Yep. We’re all of a certain age, aren’t we, sisters? Yeah. (Laughter)

MP: I have one quick question before we open it up to a couple audience questions, and it’s about what you were just talking about, about translating the materiality of your early films, where you could work an optical printer like nobody’s business. How do you translate that into working with video? The screening last night got us up into that transition, where you’re starting to work with video. And then we’re skipping over all of that, where you’re figuring it out. And now we’re here with your latest film. So walk us through that process a little bit.

BH: Well, to move from the optical printer to digital files – one thing is, it’s a lot faster. So when I was shooting Resisting Paradise in France, I would have to mail back my 16mm rolls that I had shot on my optical printer, that I took there. There I’m studying Matisse and Bonnard, and what artists do during a time of war. That was the basis of that essay film. And so I wouldn’t really see what I was doing for months, if at all. So with the digital, it’s also very creative, and very fast, and very fun. And you can just try things and then immediately discard them if you don’t like them, if they didn’t fill your emotional being. Because so much of my work is about trying to put my inside on the screen, especially the early work and the optical printing work, before I’m dealing with the other: you know, the women that we’ve talked about today, and Matisse and Bonnard.

So it’s still the creative process. One thing leads to another. And I never leave the studio without knowing what I’m going to come back and do the next day. In other words, I get up to an edit, and I know this is good, but I don’t make it. Because when I come in the next day, I’ll make it and I’ll be back in the project. I won’t be faced with the white typewriter paper that promotes writer’s block. I just love being creative. It’s just a pleasure. It’s a pleasure to make things, whether it’s digital, or material, or painting, or installation, or engaging an audience. I couldn’t have chosen a better occupation for my life. Maybe it chose me. I can embrace both digital and film. I have no problem with that. In fact, a film like No No Nooky TV (1987) was released at the same time both in film and video, and I shot with my Bolex right next to the screen, so that I was shooting the computer screen with film. And then I would take my film and project it on the side of the monitor, and re-film that. So I was really trying to marry film and digital. Film and video.

MP: So if we have a couple people who might have questions, who are willing to come on down and ask Barbara. I know it’s kind of hard since you haven’t seen the film yet tonight, but maybe you have some general questions.

Audience Member #1: So I was actually thinking, you both already addressed the first part of my question, which was: would Bishop like this film? And you’ve already addressed that, so I’m not going to ask that. Because while you were speaking, I was thinking about Bishop’s refusal to be considered not only a lesbian poet, but a female poet, right? And I remember once reading or listening to Adrienne Rich say that she got into arguments with Bishop, because she wanted Bishop to be out as a feminist poet. And Bishop was very much in the same spirit as Georgia O’Keeffe, saying, “No way, I’m going to be a poet. And I want my work to be read without that qualification,” right? Which we could discuss again.

But I guess what I was thinking was about your earlier statement about Bishop’s poetry lacking intimacy, because there’s so much intimacy in Bishop’s poetry, right? I mean, I’m thinking of that amazing poem about her washing her lover’s hair, [The] Shampoo, when she’s in Brazil. And so my question is a two-part question. First is your engagement with Bishop’s poetry over the course of making this film, and what came about, if anything, for you, reading her. And the second part there, of course, [is] this question of intimacy. Is your film also an exploration of intimacy despite the fact that she refused to engage identity politics? We can put it that way now, although I don’t think she thought about it in those terms.

BH: No. Excellent. Thank you so much for your discussion here. I think when I said there wasn’t a use of intimacy, it was more that I was missing the “I” voice. Like in [One] Art, when she breaks the rhythm of the poem and says, “Write it!” With an exclamation mark. To me, that’s very intimate. She’s telling herself, “Go ahead and make your statement. Make it from the ‘I’ place.” And sure, [The] Shampoo is a beautiful, erotic poem, and I used every single one I could find in her work, because that was the part of Bishop that I wanted to know and embrace. I guess it’s a different kind of an intimacy than in Dyketactics!, where two women are making love, and I put the camera between them and stroke them with the camera, bringing the cinematographer into the act as well.

There were some other parts to that question. Oh, my engagement with Bishop started – I got my first Masters degree in English Literature, and poetry was my love. I used to write a little poetry as well. And so returning to this film was like returning to a love that I didn’t have time to follow through on. Besides The Fish, and the few [poems] that are anthologized, I didn’t know Bishop’s scope of a hundred poems. A very short, brief kind of output of her work during a fairly long lifetime. So, the engagement grew. If you think of Sylvia Plath, and you think of Robert Lowell, and Anne Sexton, and that kind of, almost, maybe too raw intimacy. Maybe more than we want to have. I was looking for something like that with Bishop. And I think her intimacy is couched in metaphors. Like [Rock Roses] will be one of the poems that we hear tonight. But [The] Shampoo is just really, definitely a beautiful film. You can just imagine the wooden bowl, and the stars, and the hair capturing the light, during one woman caressing another woman’s scalp. So there’s another talk around. (Laughter)

MP: I think we should probably roll the film. I want to thank you, Barbara, for showing up, and I’m sorry about the time screw up on my part. Everybody want to join me in a little round of applause? (Applause)