The Mural Movement and the Black Arts Movement: The Q&A

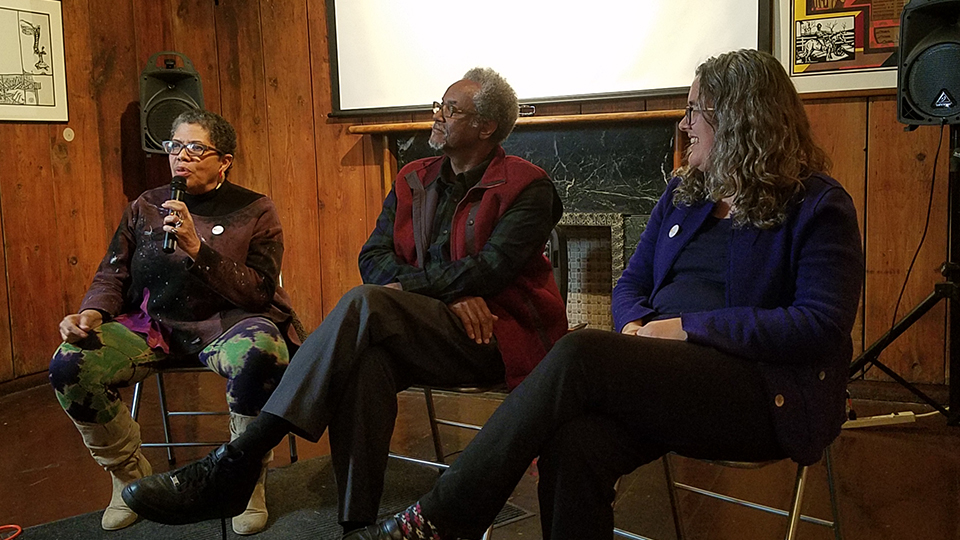

Q&A with muralists Arlene Turner Crawford and Eugene Eda Wade, moderated by art historian Rebecca Zorach, following The Mural Movement and the Black Arts Movement at the South Side Community Art Center on November 10, 2018.

The event was presented by South Side Projections and the South Side Community Art Center as part of South Side Projections’ film series Chicago’s Black Arts Movement on Film. Chicago’s Black Arts Movement in Film is part of Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy, with presenting partner The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. Chicago’s Black Arts Movement in Film is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Learn more at artdesignchicago.org.

[beginning of conversation cut off]

Arlene Turner Crawford (AC): I think the same kinds of things in terms of subject matter in public art that I do in my own work.

Eugene Eda Wade (Eda): In terms of outdoor murals, I got the concept from Bill Walker, really. Because I had thought about the idea of having an outdoor gallery, so to speak, that would be open 24/7. But it was really Bill’s idea, and I joined in because it was a great idea, and an opportunity in which you can carry art to the general masses. Many times the masses of people don’t have time, or don’t take time, to come to an outing like this, or to go to a museum, that kind of thing. So the idea that—bring the art to the people and the community, where they live. And of course the Wall of Respect was taken very well. There was never any graffiti painted on it. They protected it. As a matter of fact, we had a few gangs that were trying to take over the section, but it was never defaced.

If I’m in my studio, painting, drawing, whatever, it’s in reference to another mural painting. I do it on a small scale, but I always have in mind the general public and getting it out there. Whether I’m painting inside, like an institution, like Malcolm X [College], or whether I’m painting outside, in reference to the walls I have completed. It’s always thinking about art for the people, and bringing the people the awareness of beauty—not that they don’t have that, but in terms of my own little concept—awareness of who they are. Not that they don’t have it, but maybe just reawakening these kinds of feelings within them, so that they can continue having the pride and respect for themselves and others as well.

Rebecca Zorach (RZ): So, Arlene talked about collaboration, and Eda, you also talked about collaboration in terms of your working relationship with Bill Walker. I’m wondering about whether there are things that you can think of that were unexpected things that occurred in the course of making a mural. Apart from getting your leg broken. [Laughter] But, artistic surprises that came out of collaborations. Things that wouldn’t necessarily have come from you as individuals, but came in the process of working with another artist, or other artists.

AC: In most cases it made me rise to the occasion, because I wanted to be useful, or helpful. When I work with other artists, their work inspires me. And I like a dynamic, because sometimes if you make a mistake, or if something has to be changed, it can be done on the spot. And you just discuss it, and create it. When I was watching Calvin [B. Jones] and [Mitchell] Caton do that mural on the Regal, that was the first time being up close and personal on two, to me, great muralists. Both of them, like you, they take these little drawings, and they don’t need to throw them up on a projector. They just paint it on there, and mix the color that they wanted right there on the spot. Calvin would say, or Mitchell would say, “Hey, Arlene, mix up some yellow. Put a little more gold in it.” And that was just being able to be in a creative process in real time, and that’s what affected me.

That’s why I love doing it with community, with children, with young people. Because it’s some of the same kind of energy that they get an opportunity to be a part of. And I was just going to say one other thing about making murals. [AFRICOBRA co-founder] Jeff Donaldson one time told me that the mural movement in Chicago was like creating stained glass windows in the neighborhood. And when I asked what he meant by that, he was saying, “You create a sacred space.” And that’s what murals and public art get to be when people can be a part of the creation of it. It’s a sacred space to them. The gangs don’t mess with it, it doesn’t get in any way hurt.

Eda: In reference to my involvement, I do use both. If I’m inside the studio, I’m dealing with making the sketches and working out some of the colors. I try to have preconceived ideas in terms of what the overall thing is gonna be. I do use a grid system from time to time, covering over the small sketch with the grid, and then enlarging that according to whatever numbers I lay out, because I find that that’s easy. I’ve also used a projector to project the image from the small sketch that I’ve used.

And as Bill and I would be working side by side and creating our particular art in our own style, a lot of times I would like what he did with the composition or with the drawing, and then the next moment I’d look over and he’d wiped it out, he’d started over. I said, “You had it, Bill. Why did you change it?” He said, “You know, it just wasn’t right. It wasn’t doing what I wanted to do.” And the same thing would happen—I would have things that Bill really liked, and I would end up changing it, and he would say the same thing to me. “You know, you had it, why did you—?” I said, “It just was not right.” I had to keep working, I had to keep doing it until I was satisfied with it. So that’s how I interacted with artists like Bill, and also using the grid system to lay it out on a smaller scale and then enlarge that on a larger canvas or wall.

RZ: I just have one more question, which might be a yes or no question. Just thinking about the films, I was struck by—of course we had the film about Ray Patlán’s mural, and he was talking about Latino murals in Chicago. I think he actually backdated Mario Castillo’s first mural to 1967, I think it was actually 1968. So I think he was maybe trying to give it the same level of priority as the Wall of Respect, which it actually followed. But obviously the tradition of Mexican murals is really important in Mexico, and then also Mexican-American murals in Chicago, and in L.A., and elsewhere, all over the U.S. I noticed that Don McIlvaine also talked about the murals in Mexico. And I wonder if, when either of you were working in the 1960s or ’70s on murals, was that something that was a point of reference? Were you thinking about the Mexican muralists and the work that they had done as a kind of precursor to the work that you were doing?

AC: Yeah, a lot of my teachers told me to look at Orozco, look at Diego Rivera, and Murray de Pillars, and Bill, for that matter, when I talked to him.

RZ: And that’s Murray De Pillars?

AC: Yeah, Murray De Pillars. And Bill Walker was really always lauding the work that the Mexican muralists were doing. So yeah, it influenced me. I learned about it. I felt if I was going to be a muralist, I needed to know the history in some way.

Eda: Yes, I would say yes. Bill and I talked about the Mexican muralists quite often, especially the three great giants: Siqueiros, Orozco, and Rivera. Especially the expressionism of Siqueiros and Orozco. We talked about that quite often, and how they were able to almost wrap the design and the composition around walls, and defying that, as if the corner of the wall was not even there. We talked about that all the time, and we did look, and study. And we got books on those three great ones that we admired.

Patric McCoy (in audience) (PM): Thank you for your presentation. I wanted to ask you, because you jogged my memory, I vaguely remember the fifth stage of the Wall of Respect on 43rd and Langley. There’s nothing there. And that was obviously produced with very, very durable materials. And my understanding is that when public art is created, you can’t just willy-nilly destroy it. So where is it?

Eda: Well, that’s a million dollar question. We’ve been trying to find that out ever since it disappeared. I’ve had Georg Stahl involved in it. I’ve asked Rebecca, Jeff [Huebner], you know.

PM: It disappeared overnight?

Eda: We don’t know what happened. Have you heard?

AC: No, I haven’t, but I think I drove by there once and they were taking it down. And no explanation was ever made of it.

Eda: Maybe it was too controversial or whatever.

AC: I don’t think it is.

Eda: I don’t know, ’cause I had King going against the oligarchy, which is, you know, a corporation, you know, demanding the same types of things. I don’t know. But we’ve inquired, people have asked, but we still don’t know. All I have is pictures of it.

PM: Okay, my understanding is—

Eda: Wait, one other thing. I have a document that shows all the people that were involved in constructing the mural, the names and everything. At this time Georg Stahl has it. Is Georg here today? Do you have it? Could you bring it up a minute? So it was done, and I got the proof of that. This is the document of it. Anybody who wants to see it—here, you’re ready to look at that. I was gonna tell you about that anyway. But that’s it. It’s all documented, in terms of all the people involved, the ones that bidded on it when it was done. And Georg and so many other people have tried to contact these people, and we get no response.

PM: My understanding is that they can’t do that.

AC: They did it.

Eda: Well, if you think about the WPA program, where all those artists did those beautiful murals in public buildings and libraries, they took a lot of those and just threw them in the garbage. They can do whatever they want. They got the power, and they don’t care about what people say. You know that. That’s my opinion about it.

PM: The ones where public money is going into it? You can’t just—

Eda: You know, those porcelain enamels cost quite a bit, and the construction, yeah.

RZ: There’s actually an ordinance that they’re trying to get for Chicago to register and protect public art. There’s a lot of public art, like murals, that have been sandblasted. I think it’s a big problem in the city. The city doesn’t necessarily even know all the public art that it has. In fact, I know that for sure, because I was contacted by someone who had just started a job working for the city, who wants to get a registry of all the public art that’s in the city, and they don’t have it. So I don’t know if it was a developer, because there are townhouses there now. A developer maybe just took it out, and the city turned a blind eye to it. I don’t know.

Eda: No one ever told me that it was going to be removed. I think I went down to the wall to check it out several years after it had been removed, and I was shocked. I mean, where is it? And I started telling some other people about it. Do they know where it is? And nobody seemed to know. So we even suggested, if anybody has ever heard anything about where it is, let some of us know. I don’t know. And I don’t have time to search it out to see where it is. It has to come from somebody else. But I’ll be glad to receive the message. Somebody has their hand up?

Audience Member #2: Yeah, two different subjects. One, as recently as the last three or four months, there have been instances of murals being painted over on the north side and Near North Side, where the alderman had commissioned work to be done, but some other entity inside the city painted over it without the alderman’s permission. The second thing I have is totally off the subject. Mr. Wade, in regards to the Malcolm X doors, what’s the status on that? Do you know where they are?

Eda: All I know is that my daughter and I, Martha Wade, went over to the DuSable Museum, what was that, three, four months ago? We were trying to get something worked out where we could have a forum like this. And they had eight—or six? They had eight doors that had been donated to them by the city. Now the other doors, I don’t know. I understood that they took them from the exhibit at the Cultural Center, and carried them back to the new Malcolm X. And then, the city owns it. So evidently, six of eight were donated to the DuSable Museum. We saw those, physically. And I told Rebecca about that. So Rebecca may know something more about where they are than I do.

RZ: I think the other ones are in storage that’s controlled by the City Colleges. I’m not sure that there is a current plan to do something with them, other than keep them in storage. But I think they are safe in storage. That’s my understanding.

Audience Member #3: So they’re not a part of the newly built Malcolm X College?

Eda: No. They had talked about using some of them as a coffee table, book case. [Laughter] But I don’t know what they’re gonna do. It’s a professor over there that maybe you can contact. What was her name?

RZ: Michelle Renee Perkins, I think.

Eda: Michelle Perkins. She’s a professor over there, and she was one of the key ones that helped make me aware of those doors. In fact, the old Malcolm X was being demolished, and, what’s going to happen to those doors? So I asked Rebecca to help out, I asked Jeff, Georg. I asked whoever I could to help her out, because she was fighting kind of an uphill battle in reference to those. We didn’t know whether they would be saved or not. But because of people like Rebecca, and Georg, and Jeff, and some others that called them, and talked with them, and emailed them, they had to try to decide on, “Okay, maybe they are important to save,” and all that. So as a result of that, I think, they were saved. But the City Colleges here, they have complete control. That was a commission that I worked on, they paid me, and that was a two year commission. So I don’t have any say-so as to where they’re gonna be, what they’re gonna do with them, et cetera, et cetera. It all belongs to the City Colleges. Maybe you can write some of the politicians and get some answers for yourself, I don’t know.

Audience Member #4: I really liked the part in one of the documentaries where there was a guy painting a mural, and he was talking to the kid. And I always wonder about space when thinking about murals. Not just the artwork itself, but the experiences you have at the wall, whether that’s while it’s being painted, or after it has been painted. Can you all talk about any experiences that you’ve had, or that you’ve heard people have, that speak to the importance of the space that murals create?

AC: Well, yeah. The murals that I’ve been a part of, those that have either been inside or outside, there’s been people whom I’ve had the opportunity to discuss the mural with, or talk to them about. People who have come by the project and inquire what you’re doing or why you’re doing it. To me, these kinds of experiences help strengthen the piece, and one of the reasons I like doing it.

I appreciated that part of the film, too, with the discussion. ‘Cause I try to do that, when little kids come and talk to me about it. I like to give them some history, and let them know who I’m trying to portray, and why I’m trying to do it. Give them a little sense of the history of the space that we’re doing this in, and some of the reasons why. And I find that, like I said, it helps people get a connection, get some ownership, and that’s to me the real purpose of public art. To have these interactions, to have something that—if it still stays up, over years, or decades, or a long time—people can be griots about it in their community. “This piece was done back then,” “I remember the artist coming out,” this, that, and the other. And that helps, I think.

Eda: Bill and I used to always entertain the little ones passing by, the old ones, middle ones, whatever. If they asked a question, we would stop, and we would talk, and answer whatever question. And some of them was not all that positive, ’cause I had a lady come by and ask me why was I wasting my time drawing those mural paintings with all the talent I had. I told her, you know, “I’m giving back to the community. That’s part of my contribution. It’s something that I want to do.”

But nevertheless, much of it people understood. And they were proud to be a part of that, in terms of, it’s in their community. Especially when all kinds of people started coming out and visiting the wall. And even now, I wonder, what was so important about the Wall of Respect? And I know, I worked on it, and did my part on it, but I’m just being honest. I still wonder, why was it so important? But the people who would come down, all hours of the night, all types of people, they would be coming to see. And so the people in the community began to appreciate it more, because they said, “Well, if all these people are coming out, this must be important. It must be something.” So they began to appreciate it and like it. But, frankly, I’m still trying to figure out what it’s all about. [Laughter] What is so important about it?

AC: Well, when it happened it became a spot. It became a place. It became, just, alive. Music happened there, theater happened there, spoken word happened there. People began to talk about current events there. It kind of galvanized and gave an opportunity for people to discuss things with each other, and be a part of a culture that was going on. That’s what impressed me. That summer I had come home after the wall was done, there was always something going on down there that I wanted to see. AACM was playing there, musicians were playing, or speakers were talking. Dr. Gwendolyn Brooks was reading things there. So, it was cultured, it was something you could just be there and be a part of. And that’s why I think it inspired people. The Wall of Respect made our community something we respected.

Eda: It wasn’t all peaches and cream, I can tell you. [Laughter] You had gang bangers down there, you had prostitutes, pimps, drug dealers, trying to con us and whatever else. But Bill and I grew up through the ranks, so to speak. We knew it. They couldn’t con us. Not that we were con artists, but they couldn’t. We had heard it all. And we also was willing to just be there and give our life, if it took, because you had people literally shooting down there, shooting at each other. You know, people dodging and falling down. We worked there, and I’m just giving you the total picture of that. It wasn’t all peaches and cream, where everything was hunky-dory, so to speak. So that’s the other aspect of it. But I think I’m beginning to understand, maybe, a little better. [Laughter] Maybe it’s historical, and et cetera, et cetera.

Audience Member #5: You’ve worked recently with [Rahmaan] Statik, and Max [Sansing], I know him as Aeros. So can you just reflect on how hip-hop, and the graffiti movement, and the street art movement, has either enhanced or built upon what you all were doing?

AC: You know, I think it’s, like, a transliteration. I remember—and Statik doesn’t remember this, but I just recall that the first time I saw Statik, he was doing those spray painting murals in the alley, where they had opened up that space. I live in that neighborhood, and I just love the idea that we were having art being made fresh and new. And every year, every summer, a new gallery would appear.

So yeah, I think when hip-hop came into this mural movement, it moved from the idea of tagging space and just putting out your name, to, it kind of embraced some of the purpose of what the Wall of Respect was doing. Tagging with some imagery that was current, or that was prideful, or was in control of a new set of thinkers. So I think that the hip-hop art, and Max—I’m just amazed how well they can do with spray cans, and how fast they work, how the technology has also helped the imagery. So it interests me. I like seeing those artists who do have some positive things to say, or are using the media to push the envelope.

Eda: But most of the people—I want to put this positively—most of the people were family, folks with children, and they were just trying to make a decent living and whatever else. It just had a few rough, bad elements around that made the whole community sound bad. Especially when mainstream media used to always play up the negative things that were happening, when somebody got killed, et cetera, et cetera. All right? But most of the people there were law-abiding citizens with family, working hard, going to work every day and trying to raise their family and do what they could.

RZ: One last question. There.

Audience Member #6: With respect for the essence of the murals, there has been a question of graffiti as opposed to art. And our general community is not really educated to fine art. This representation here was in the nature of elevating the culture of the community, in the sense that, in the ancient periods, you have art that has lasted over the centuries, many, many years, when we go back archaeologically and discover what was going on at that time.

We have to take in the context of what was happening at the time that that happened. That was when we were really in a Jim Crow era. We were in the midst of the civil rights movement at that time. So the community had an opportunity to see a large representation of what our culture really was, that was positive, as opposed to everything at that point being done by the media, and our good Mayor Daley, who was negative about what was our stature, what was the right aesthetic. And that, I think, was a historical movement at that time that we had hoped would remain there, so we could always go back historically.

Eda: The whole wall, and area, had names of gangs and names of other things all over it. And I give Bill the credit, because it was his idea, he drives through that community every day, he knew the people. And he said, “You got all this graffiti on the wall.” He said, “One day I’m gonna do a mural painting, and do something beautiful, and wipe that stuff off.” That was his idea. And so he came up with that idea of removing the graffiti to make it beautiful, and to paint something that people could be proud of and identify with. So as a result of that, you’re absolutely right about what happened, and what can happen, and what did occur. So I give him the credit, because it was his idea. It was a good idea, and a lot of us wanted to have that idea, but most of the OBAC members would give Bill credit. It was his idea. Some of them may not, but most of them would.

RZ: Arlene, did you want to respond to that last question?

AC: I was just gonna say that art is transformative. And it will hopefully continue to be. And the black community hopes to be in charge of how we transform our art and culture. And that’s just maintaining our space here, and helping to push it forward.