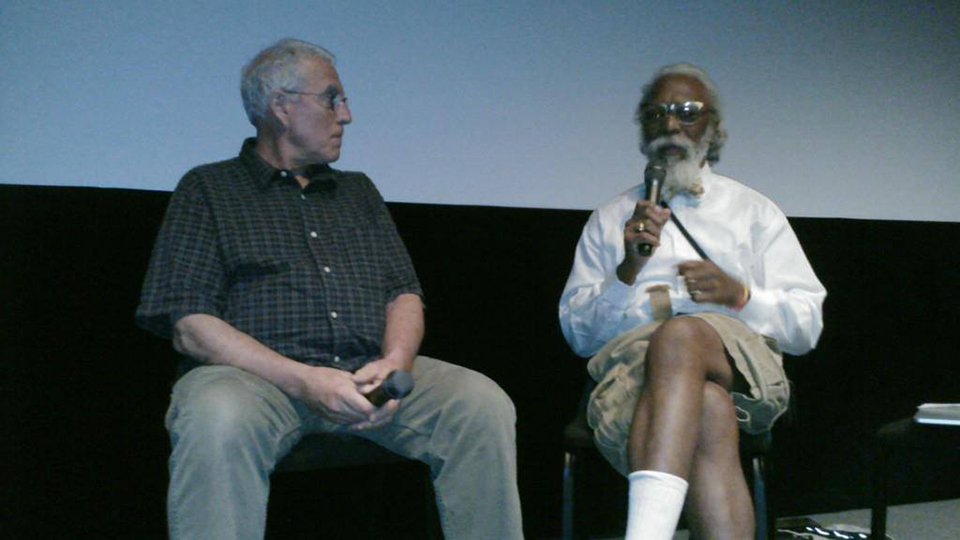

Revolution on Film: Peter Kuttner and Travis Q&A

Artist and Vietnam veteran travis and filmmaker Peter Kuttner speak after the August 9, 2013 screening “Revolution on Film: Black Veterans” at the Logan Center for the Arts

Michael Phillips [MP]: The two films tonight, one was made right here in Chicago, Trick Bag was made by the Kartemquin Collective. We’re really happy to have Peter Kuttner, one of the filmmakers, here to discuss the film. And the second film is called No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger. It was made during an anti-war march in Harlem in 1967 in conjunction with Martin Luther King Jr.’s UN speech where he questioned the disproportionate number of black soldiers fighting in Vietnam. So we’re gonna watch the films, and then Rebecca Zorach, who curated the AfriCOBRA exhibit downstairs, will introduce our two guests. Our second guest is artist and noise-rock performance artist travis, who happens to be a Vietnam vet, and Peter Kuttner, and they’ll have a conversation about the films.

Rebecca Zorach [RZ]: So, I’ll start by introducing Peter Kuttner, who has worked in mainstream and alternative media for over forty years: he worked at WTTW, he was a member of Newsreel, and his commitment to politically- and socially-engaged filmmaking landed him at Kartemquin in 1972. And his projects include the film that we saw at the beginning Trick Bag, Now We Live on Clifton, and UE/Wells. He was also a founding member of Rising Up Angry, a number of members of which appear in Trick Bag, and that was an organization of working-class youth. So he really, I think, has lived the—immersed himself in—some of the subject matter he’s dealt with as a filmmaker.

travis—and that’s his full name, and there’s a story there, but I won’t ask him to tell it tonight—is a painter, performance artist, installation artist, noise artist, gardener, traveler, and decorated six-year Navy veteran, from 1963 to 1969. He’s Vice President and Treasurer of the Chicago chapter of American Veterans for Equal Rights, which promotes the interests of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender American veterans. He’s had many exhibitions in Chicago and elsewhere, he’s been a 3Arts Ragdale Fellow, he’s had exhibitions here at the UofC and at the South Side Community Art Center, and I think maybe he actually has some artwork to show us as well.

The question that I wanted to ask to start out with was just to ask you both to reflect on what seems to me a kind of divergence in terms of the way the stories that we tend to hear of the civil rights movement and the peace movement, the antiwar movement, in the late ‘60s. We tend, I think, not to hear as much about the convergences or the overlaps between those movements. I think when you hear about anti-war activism, you think of—the sort of the popular imagination is to think of white college students. And it’s just really striking to see in Trick Bag, to see the connections that are being made among working-class youth and the ways they’re kind of thinking across racial lines, to think in terms of class-consciousness. And then in No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger, obviously these connections are being made very strongly, and very powerfully, between what’s happening in the War in Vietnam and what’s happening at home. So I just wondered if you both could reflect on that: we’ll start with travis.

travis [t]: Thank you. First, I was born in Mississippi, 23 of September 1946. And that’s relevant to all this because I am a sole-surviving son: I have three sisters. I didn’t have to go to Vietnam as sole-surviving son, I decided to go on my own. We had moved to Ohio, my mother had moved us to Ohio by then, that will become more relevant as this continues. To the point: there was so many more issues than even the issues of activism. I was in from 1963 to 1969, a highly transitional period in American history. There was so much going on, everybody wanted to talk about freedom, about liberation, about all of these things. So by the time I got out in 1969, the world had changed radically from 1963.

But when I got out, I was stunned by how much hatred there was for me as a veteran. And there were reasons for that that I knew about, I was in communications and I understood that there had been the Tet Offensive, [amway] and all of those, and many American lives had been lost just before, and during, 1969, and Americans were really quite fed up. So in the street, I went back to Akron University. And Akron University is just near Kent. I was at Kent State, yes, when it happened, but Akron University and other universities were highly caught up in all of this. There was women’s lib, there were all of these overarching ideas and people were being complete—not to mention gay liberation, which was also a very big deal for me, because I had a highly classified, a high-security clearance.

And in 19-, on my 19th birthday, the Office of Naval Intelligence decided at some point I had, in my nineteen years, I had committed sodomy. And I was pursued for all those years—lie detectors, the whole nine yards—trying to get me to confess to having committed sodomy, or to try to find out. And so all of that was following me into Vietnam; and so when I got out, there was just radicalism, everywhere. So, yes, I fell right into it. I was quite at home because I had to find a place: as a veteran, you had to find a place. You were hated, you were the despised. And there was really no reason to live, as a black veteran, unless you were engaged. But so many people were so traumatized by the war, you had to find specific engagements. And so yes, there were many many other levels to the films aren’t there, and I was got right in the thick of it. And I’m happy to say that I found a place in it, in art. And I’ll stop, I’ll come back later.

Peter Kuttner [PK]: Um, was born in Chicago in 1943, and this is important because when I got drafted, I’m not going to say there wasn’t a Vietnam, there was a secret Vietnam, I got drafted before [the Gulf of] Tonkin [incident]; I never heard of Vietnam, I was fully prepared to go in the service to learn a trade. And I failed my physical, and got something called 1Y—they weren’t giving 4Fs anymore because they knew there was a Vietnam and they knew they would need more, but for some reason I never got called again. I sometimes feel that the can of pop that the draft guy was drinking he put on my folder and then some other one got stuck to it. But I never got called, and I realized then after Tonkin had started to heat up, I wasn’t gonna call them and check it out. I liked to travel but I didn’t think I wanted to make that trip.

But then it led me, I started to learn a lot more about Vietnam, and realized that that could be me there, and I didn’t go. And I knew guys who, it turns out, who did go, and I lost a couple of them. And I don’t want to say that I was moved by guilt, but I certainly started to pay more attention to what was going on in Vietnam, and got drawn into the movement. So in the sense I am a veteran—not a black veteran—but I am a veteran of the war in Vietnam in that I was in the street with…some people I see in this room, actually. And in the street, we learned that there were young people—not unlike the people you saw in the film, with the leather jacket, talking about how Asia was for yellow people and all of that—who were interested in what was going on.

And as community organizers, we thought that there was something going on in those communities that some of us had grown up in. I grew up in Lakeview, in the neighborhood that was officially known as “Over by the Ballpark” back in the days before there was gentrification: now known as Wrigleyville. Went to a public high school that drew all the way from rich kids on Lake Shore Drive, out west past Western Avenue, and drawing in, literally, poor kids from Uptown. So that some of these students you’re talking about, that I ended up marching in the streets with, had read that in books. And not that I didn’t read books, but I didn’t read those books, and I felt that I got that class analysis, that they called it, just in the public school system. And what really got me involved was that I knew people, I met people that were organizing at my old high school.

And, then as we start to meet some of these people that were a few years younger than us—I’ll refer to them as kids, and maybe I was a kid then, I don’t remember anymore—that when we met the vets, the white vets coming back, who had grown up in racist situations—I’ll give you an anecdote about one in a minute—we learnt so much from them, about how their views towards people of color had changed while they were in Vietnam. You saw my friend Al in our film Trick Bag, who found himself—its funny, ‘cause a lot of the young men who we met that had changed the most, had been in the brig or the stockade, which were overwhelmingly filled with African Americans. And soldiers of color, and only a few white guys in there: they came out the least racist of all, it seems.

Young man named Tom, who we met, and became part of the organization, had been in Long Binh Jail when it was burned down. And this guy is a—I don’t wanna call him a poster boy for anything ‘cause of where he came from—he grew up in Gage Park which was really the typical changing neighborhood. And was thrown out of Gage Park High School, the public school in that neighborhood, for “race agitation.” Young white man, for “race agitation.” And has his choice: he gets into trouble and has his choice to either go into service or to go to jail, well he picks the service. And he gets into service and all the white guys he finds in the service are farmers! And this is a guy wearing a leather jacket, listening to Motown, talking an urban talk. And it wasn’t so much a question of race anymore, it was a question of “who’s like me, here”: and it was all the black guys that were like him. Not the white guys. And he fell in with them and he ended up in Long Binh and they burned it down, and he comes back and goes back to Gage Park with a whole different attitude.

Not like he was in the movement, but he was now a respected guy in his neighborhood of thugs and when they’d say “well, let’s go to the other side of Ashland” or whatever the line was then, “and make some trouble,” he’d say, “wait, that’s not so cool anymore.” They’d say, “wait a minute, before you went, you were into that.” He’d say, “well, I’m not into it anymore.” And we met lots of guys like that. So, on the question of Vietnam, they were very good. ‘Cause here we were, going into neighborhoods, saying, “we want the guys, who are after your brothers and your cousins and your uncles, we want those guys to win.” This was not…this was a hard argument to make.

And when you went in to say we were…in a sense, Rising Up Angry came, was born, actually by somebody you see in the film. As you pan across the lead marchers, right in the center you see Stokely Carmichael. Stokely Carmichael was head of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, known as SNCC. And basically SNCC says, around ’65 or so, right around or after Selma [the 1965 civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery], says to the young white people in there, “we don’t need you. There’s enough racism up north, go up north and do your own stuff.” And in a sense, Rising Up Angry comes out of that. So, Rising Up Angry is sort of an anti-racist organization, at least. So that’s what that film—let me just finish, well, this part of what I have to say—that’s what this film is. This film, Trick Bag, which we shot around, in the early ‘70s, I think we started shooting around 1971. The film got burnt up in a fire and took a long time to make partly because of that. The attitudes in it are 1971, ’72. We didn’t finish it till 1975. It was to give an example: it was the days of the hard-hats, all white people are racist, all hard hats, working class white people hate black people, they love the war in Vietnam. And we knew that not to be true, and that’s what that film’s about. It’s that step in the process. It’s not like we’re all revolutionaries, it’s that, well, we realized that this whole racism thing is a trick. Hence, Trick Bag.

Audience Member: What was the response to the film when it first came out?

PK: It was really remarkable, I thought. I thought we were making a little organizing film that would be used by this Rising Up Angry group, and by the time it was made, Rising Up Angry had sort of gone away. ‘Cause the war went away, the anti-war movement went away, the government had fairly successfully smashed the Black Power movement with COINTELPRO and assassinations of black leaders. And there was not really a use for it, I thought. There’s no more Rising Up Angry, what are we gonna do with this film? But it really took off, as, I don’t know if you could consider it: in those days there was no video yet, and there was no cable TV, there was no internet, it was a film on a reel and you needed a place like this or a wall and a machine to show it. And you couldn’t get many people around. But as word got around what amazes me is that—and it’s unfortunate—it’s still useful today. I met a man recently who teaches community organizing in San Francisco and he says he uses this film all the time. You’d think it would be dated, I mean, with the music, with the language, but it seems to resonate, even if you don’t know who Jane Fonda is. I always cringe when that part comes up, because that really dates it! “Who was Jane Fonda, anyway?”

Audience Member: One of the things that struck me was from Trick Bag. I’m listening to their talk and then I’m thinking about, I think some of the things that people said were “bring the war home,” that the issue’s here. And I think, OK, so it’s 1975, the war ends. By 1980, Ronald Reagan’s president. Three decades later, there’s more prisoners in the United States than there are anywhere in the world. Social trauma is so deep in some communities that when we think about somebody who does one tour in Iraq or Afghanistan, and the post-traumatic issues that come up, and then you think, what if you spent 16 years in a neighborhood where, say, by the time you’re 8, you’re sort of watching every single car that comes down the street. Or the police have to touch you inappropriately, or push on you or beat on you, “oh, we have 29 activity cards on this person,” you know what I mean. What’s happening to young people, just the level of attacks that are leveled against young people in some communities. I want you to talk about that a little bit.

t: Well, I always think, I just saw No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger two days ago, when Mike sent the link to me. And I look at it and think, well, gee…the issues that are raised are more extreme now! Why are they more extreme now? Well when I got out of the military, I went back to Akron University, and you had to get involved in something: I was marching. Getting tear gassed in Washington for antiwar demonstrations and all of that. Trying to find a reason to just live in America. I’m Native American: issues are much deeper for Native Americans than they are for even blacks. Now, here, I looked at the film, and said, here I am in 2013. How many of these issues are still relevant? All of them, plus. And I asked, I had to really think about what I had done, or not done, to become aware of why things were the same and more extreme. And why, in my community, so many more people now have a mortgage, that means that they are less engaged with issues now. And why now do most Americans feel that there are no civil rights— that full equality has been achieved? Blacks and whites! That means that I am responsible for my behavior across the board, and the past doesn’t matter.

Well, when I was back at Akron University, we had to look—and people were ugly back then, in ’69, in Akron and Kent. Akron was conservative, Kent was not, and I was on both campuses. One thing that you had to do to get involved was become acutely aware of what was the military industrial complex and how it fit. And that was important to me then, it remains important to me now, because the people who owned and ran the war are still here. Bigger, better, more flowering that ever! Has that no relevance in how we change, in how I live my life as an ordinary citizen? In who owes me and who can live and who shall die, and what our children talking about, as long as we can stratify, and keep the community stratified, then the battles can be fought out there. There’s also another issue that becomes relevant, and that is not just the military industrial complex, but the military industrial academic complex, all working in tandem. How do I, an ordinary citizen from Mississippi, say that I have any chance at freedom? I don’t. And I don’t think, therefore, that there is radical change that we can really expect. I think that there are wonderful things that do happen, like understanding what your pathologies are. Understanding, and I worked with Rebecca [Zorach] a while back, understanding that change in communities can come through art and radicalizing art in the street can be fun. And it can let people know, and it can also send a message to “leaders” in the community that you are not going away. Your turn.

PK: The political movement then, and by its nature Rising Up Angry, was dealing with all the issues in some way. It started as a newspaper, in reverent imitation of the Black Panther newspaper. It also had—I think I didn’t get into that part—we were very influenced by the Black Panther party, particularly the one here in Illinois, and Fred Hampton was a real influence, an incredible spokesperson and hero to us, even before the assassination. He really spoke the truth, he did it some way, he may have been eight years younger than me at the time, or seven years, but he was the wise man at whose feet we wanted to sit. He just knew how to cut through all that rhetoric, somehow, and say it so clearly. So, we also had our free health clinic and our free legal clinic and things.

But when it came time, we said, well, I have these skills. And I got together with this collective that has gone through all the years as Kartemquin Films, and we said, what will we—Rising Up Angry dealt with all these issues, all these: imperialism, women’s liberation, black power, racism—we can really only make a film, ‘cause we didn’t have the access to the equipment the way that everybody has today. You can make a film with your iPhone, and in fact some of that film looks like it was made on an iPhone. But, so we had to make a choice, and what is going to be the thing…what’s going to be the hardest of all those issues? Well, we knew the war was gonna end, but we said race is the one. All of us coming from Chicago, knew that that hadn’t changed in all those years, even with the movement. The young man who I met who burned down Long Bihn, claimed to be a classmate of the man who ill-advisedly threw the brick that knocked Dr. King down in Gage Park. What had changed, just in those years? So we somehow came across, decided to make it about race, and the sad thing is that it resonates still today.

t: The issues of race, I think, have so many more facets in the black community, and probably very different meanings than they do in the white community. There’s of course this thread, but something that I deal with continuously, and have since, well, when I got out there were essentially all of these issues that were just burning in the street. My first trip to New York City was the weekend of Stonewall. I walked into New York City and it was like a third world country, in the East Village. And it was stunning. There were all of these queens in all sorts of attire, overturning police cars and fighting like people I had seen, I was in Cuba, I had served in Cuba, Cuba was where I spent my 19th birthday, and I spent an entire day of interrogation, with straps and electrodes and all of that, with the Office of Naval Intelligence trying to convince me that I had committed sodomy. You do not even use that phrase in the black church in Mississippi. You do not. It is simply an…and of course with the lie detector, it’s your pulse and your emotions, and I spent an entire day, it was the most extreme day of my life so far, and it has transformed me from that moment until the very moment that you see me here. It is a very difficult time. And I had never committed sodomy, I didn’t even understand what it meant. And here was…the Navy, the military, convinces you in boot camp that they are your mother, your father, and your family. And you sign all of that away. And to be seated in a room, for an entire day, with straps—I have never… it started 8 o’clock Monday morning, I get a call from Mr. [Montson], I go to his office, I am seated there, and from that point until the end of the day it’s sodomy, sodomy, painting the most extreme pictures in my head and I’m answering them. I’m trying to imagine them for the first time and I’m answering him.

And when I left that evening I was totally changed, forever, forever, from then, my 19th birthday until my 67th birthday this year, I have been changed. My ideas about sex and gender changed. My ideas about pleasure and pain changed. My ideas about humanity changed. My ideas about god, and where was god when I needed him. Because I suffered. And I get back to my barracks, and six people that I knew— and in Communications you all sleep in the same space, you go on liberty in the same, because you have high security clearances. I get back, six people that I knew closely had disappeared from that day until now, and their names were never spoken again. Their beds were turned back, their lockers cleaned, names removed and no one ever spoke their name again. And that was the first time, and that continued throughout the time. Somehow they were convinced I was a sodomite: what that meant for them I do not know. But for the past thirteen years I have worked with American Veterans for Equal Rights, to see that DADT [Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell] was overturned so that somebody else does not have to deal with the kinds of things…so that as an issue, was in the street.

In 1969, I go to…ship is about to go back on tour. I then decide, no, the command decides, that I am to be moved ashore, so I then make a great transition because at the end of that year I get my discharge—honorable discharge, thank you—no sodomy anywhere to be found, there are no bones to be found, I have never done what it was assumed that I had done, for if I had I’d probably be dead by now. And furthermore, out of that I get to New York City and there’s all of this radicalism in the street and people are talking about the kinds of things that the ONI [Office of Naval Intelligence] have accused me of. That was very odd. Very, very peculiar! So I then begin to understand a bit more about issues that people were talking about in terms of race.

Because in the black community, there’s a clear distinction between the queer and non-queer personalities, in 1969. I mean, you wouldn’t even call it queer: the idea of being gay, and I’ve never understood that term. I understand queer because it’s radical, and I’m willing to fight, and die, but I’m not willing to have anyone assume that I am exclusively sexually attracted to men. And so, the ideas that are in the street by kids and everybody else in New York City and in these, in 1967, the time of this movie, yes, are about race, but there’s this subtext: well, what about sex and gender issues? And I think there are very big issues now, and still, because black preachers don’t deal with it very successfully. They cannot somehow deal with it. Jeremiah Wright is fine with it, but most black preachers don’t deal with it, most black veterans have no support, most black veterans who were queer are dead. No support. Dr. King’s movement was really on one level the work of a queer man, thank you. And Dr. King’s preachers ran Bayard Rustin outta town, and they are still around. The work continues. And so this idea of race, I think there’s this idea of race there as well. Because that was a very big deal in the streets in 1967, ‘68 and ‘69. And let me shut up and let you talk!

PK: Talk about a hard act to follow! We see a lot of it in the film, and I grew up with it believing that it was going to be bloody, it was going to be violent. We’ve revised the history some, in that, to the so-called revolutionaries—and we called ourselves that—Dr. King was not the hero to us then, that he is now. He didn’t go far enough. Stokely kind of led us that way, the Panthers kind of led us that way. In retrospect, it’s a little different. So, anyway, I feel like I have to be personal because you were so personal, and gave us so much of yourself there. That, so coming from these years of thinking it was going to be a fight, a war, Rising Up Angry, and a lot of us, were maybe more concerned about the race war than we were about the Vietnam war. ‘Cause we had a certain amount of humanism about us. But I feel, today, very different. I don’t have guns anymore, for one. I realized I couldn’t use them. But at the risk of being really simplistic, I wanna quote to you a statistic that I read today—I have to be totally honest, I read it in the Red Eye, which happened to be sitting at the bus stop while I was waiting for it—but it said that 30%, or a third, more than 30%, of Americans under the age of thirty who are in committed relationships, this is gender-blind, are in a relationship with someone of another race. A third. And I think that that’s gonna finally turn the tide, is that: people loving each other.

t: You think this was the fear, of those in charge of our United States Government, during the ‘60s? And by in charge, I mean, that whole military industrial academic, and the people who were in charge including congressmen, do you think any of this is happening on that level now? Was any of the fear then?

PK: Well, I think that, and Vietnam had a lot to do with it, it changed the view of young people. In terms of, you come back, and you’re a white guy and a black guy saved your life. Or you just smoked dope with them, and it just cut that whole thing. The line, again, if anything, Trick Bag is simplistic, it’s not really deep in its analysis. But that line of “hey, we’re in the same boat,” the guy in the factory over at Schwinn, says “we’re all in the same boat, and we realize it.” And so it starts to be, and I gotta say, this is partly personal, because I have mixed-race grandchildren. And I have a younger daughter who’s in a mixed-race relationship. And I see it, when I travel, I just see so much more of a mix than I ever did growing up here. You know, in what I think probably is true, that we’re still one of the most segregated cities in the country. I remember in 1965, in the early poverty program, I was on campus at Dillard University in New Orleans, and amazed at how integrated, to use a term from back then, that New Orleans was compared to up north where we were all “intelligent.”

t: Go to Mississippi, it’s where I’m from, where there are fewer than 200 people—I’m from out in the country—but then, this idea of racial integration was always somewhat hidden. In fact, certain things are worse now because of integration, but there’s a bit of both. There are two points. The first one is that in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition here, Chicago boosters sold the city with the phrase, that those who invested in the city, in Chicago and its fair, should do so because blacks and Native Americans should be considered, and this is a quote, “temporary forces upon the urban landscape.” And I’m wondering how we got, what forces allowed us to get from 1893 Chicago’s boosters mentality, to the fact that there are 30% integration. But in Mississippi there’s such…I think it’s because in Mississippi old white women and old black women know everybody’s business. They know everything, who your daddy was. Because over time, there’s been a lot of miscegenation, but people don’t talk about it. But when my aunt died and three-quarters of the church was white, everybody knew. ‘Cause I asked the ugly questions. And yes, there is probably that, there’s a great amount of change because of it. But there, as one looks on the internet, when you read articles and there are comments, when I read other people’s comments, I am stunned how much further we have to go.

PK: Any more questions?

Audience member: So there’s at least one time in both films where I see what might be considered—for fear of oversimplifying things—a “united front” start to disagree about something. So in Trick Bag, I think it was outside the Schwinn shop, when one individual talks about the white foreman and how he holds us down, and then it transitions to another guy who’s like, well really, it’s the Hispanics that are worse off than us. And then in the other film we see it on the street corner between those two women, where the one lady, her two sons are there and the other lady’s very taken aback because she’s spouted off all of these things about it but doesn’t really know the situation as well. So I’m curious to hear you guys talk about times when, in your experiences, these united fronts had dissenting opinions, and how they sort of grew based on those dissenting opinions. How they sort of confronted each other within the united front and then grew based on it.

t: On a united front…well, I’m not sure how united we can be, in a country which values loudness. That values the timbre of your voice, I’m not sure…I think that very often there’s disagreement for the sake of publicity. Now, in my experiences just getting out as a veteran, it was really one for watching people protest in the street, carry on, and then when I asked about, and then, especially women’s lib issues. Women’s lib was very big, well, very big at Akron University. I jumped in, and the big issue was that women should be allowed to go to war, just as men do, and they should be able to do this and that, and I was just back from Vietnam, even aboard a ship and it was ugly there. And I stood up and I asked the ugly question, well, if you’re a woman and you want to be vocal in all of this, why not say let’s get rid of war, altogether? For men and for women! So why do you want to have babies and then go kill them! And then everybody got quiet.

But it’s that kind of thing that isn’t so much a coming together of forces, but I think that it allows people to make a leap, some sort of leap. And not just accept a certain paradigm. That we can do this bigger, we can be better at this. If I’m going to go out and wage a war, a big offensive, why not slash and burn and create a whole new area. Why not do something that my children will not have to, at least, undo. They can feel that I have made a stance based on a very strong and dynamic opinion, on my own. That doesn’t approach your question but it is my understanding of your question in my own personal experience. The kind of thing that was happening, and that was just with women’s lib. I asked the same a bit later when people were screaming about gay marriage and all of that, and I said one out of two marriages don’t work, in a country that designed the system to work for marriage! Why do you want to get married, why not create a whole new dynamic, call it something else! So, same kind of…

PK: The women on the back porch, I think it’s the final scene in Trick Bag, there’s the conversation of, they sort of say, once you realize you’re in this trick bag, and you all get together, I think Lydia says, “that factory’s gone.” Meaning all the power’s gone. I think the danger of the united front was really behind that COINTELPRO and whatever forces assassinated Malcolm, whatever forces assassinated Dr. King, and Fred Hampton. Fred, by the time I first heard Rainbow Coalition had came from Fred and the Panthers. [audience interjection] Sure. This room, by the way, is filled with white organizers I know, who have dedicated their lives to this conundrum of race. [audience interjection] Oh, that’s true, I have a guest here that didn’t know it: the counter intelligence program that the FBI devised to keep, I think in their words, a black messiah from rising out of the community. But the danger, from what I understand, of these black men, these black leaders, was calling for that united front. Possibly that was the real danger, and that’s why they’re dead today, and unfortunately COINTELPRO kind of succeeded in a way, of smashing a movement. And over the years I hear a nastier racism between communities of color, that is remarkable to me—maybe, again I’m a little naïve. But the powers have somehow set these neighborhoods against each other. Anyway, I hope that answers your question. I think there’s more…

Audience Member: The other question that I wanted to ask, to the producers of all this program, the AfriCOBRA exhibit and the other workshops and opportunities for all this discussion: do you have any more plans? Because this is a rare discussion in Chicago of late, issues of race. And I think that you stirred something up and I’m just wondering, once you close it down, what does that mean? Because it’s very important! And I think that race is a major issue in this country, in this city, and the more opportunity that we have to share and to discuss, the more opportunity we have to begin to resolve this very, very basic issue. And I’ve been in Chicago a long time, but I was in the Civil Rights Movement and I’ve been in Mississippi and I’ve been jailed, and etc., etc. But since I’ve been back in Chicago for the last twenty years, I have not had the opportunity to have this kind of discussion broadly. Black people talk to black people, and probably maybe white people talk to white people, but we don’t talk to each other. So I just want to commend you all, for this whole program: the art, and the discussion, the film, etc., etc.

[audience applauds]

RZ: Well, thank you. Thank you very much. I would say, that as the curator of the exhibition it really was a goal of mine to bring communities together around the exhibition. And doing it here at the University of Chicago, on the South Side but with kind of connections with other parts of the city, I hoped would actually create some of those kinds conversations that you’re talking about. And I feel, you know, I don’t work for the Logan Center, I teach at the University, and I’ve had a wonderful collaboration with the Logan Center staff. And I do really feel that the Logan Center—from Bill Michael, the director, on down—people have a real commitment here to fostering these kinds of conversations. And so I hope they’ll continue. And South Side Projections, also, which did the film series, is also committed to having those kinds of conversations. So I can’t promise anything about specific future programs, and what exactly they’ll be, but its something that—it’s very important to me, personally, and I think it’s important to a lot of people in this room, to keep these kinds of conversations going. And to have them be across communities, across racial divisions, and to really just address the…I’ve hoped to be able to address some present issues, through this discussion of the history, because it allows for this kind of broader perspective. But I think there’s so many issues that continue to be pressing, that are—and even more pressing than they were in the late ‘60s—I just, I hope, I hope this kind of thing will continue. And I do think that there are other organizations around the city trying to do similar kinds of things, but maybe our efforts have been, so far, too piecemeal and not connected enough.

Audience Member: I can maybe speak to that briefly—I’m a curatorial assistant here at the Logan Center—the Du Sable show is of course up until December 29th, and we are very excited to continue the conversation. We love the programming. So our next exhibition is called The Distance Between, and we’re dealing with artists who deal directly with race. We’re working in a residency in Washington Park. And that opens, actually, in two weeks. We’d love to have you, we’re having a big celebration on September 15th. And after that, a Black Collectors Collective will be our exhibition. So there are people who are on the south side who are devoted to investing in black artists. So the conversation, definitely: the Logan is very invested, and looking forward to it.

Audience Member: Hello everyone. I just had a question for Peter, basically, you had mentioned earlier that you feel that interracial relationships are an indicator that racial equality, or that concept of racial equality, is moving forward, or is progressing. If I understood you correctly. In my experience, it’s actually kind of something that people will use to minimize the racial disparities that still exist. And I’m from Florida, so everyone forgive me. But I just kind of want to understand, maybe, what do you think it means in 2013 for that experience, interracial relationships, to kind of still move the fight for racial equality forward.

PK: Well, it’s really an economic question, I mean, that whole…my brother travis kind of sandbagged me here and I got into that whole love feeling that he was, human and love thing. But, years ago, with Trick Bag, what we were trying to say was it’s an economic thing, it’s not a race thing. What I like about this “a third of the population,” means that it’s starting to, that personal animosity or whatever that is, wherever racism comes from, it’s not real! I mean, there are arguments about race not being a real thing, it’s this imagined thing, well, not so much imagined, but manufactured is probably what I want to say: manufactured by people who will profit from it. It’s not in our interest to do it, it’s not in our, all around the world, it, how it works, how it’s helped the power, that 1%, if I can borrow the newest movement’s terminology, is by its exploitation. I don’t know if that really answers your question, but I mean…I don’t really think that interracial relationships are going to solve the root problems behind racism, it’s a wonderful side-effect, I think, that I’m really thrilled with. I didn’t realize when I said that, that my granddaughter’s actually in the room. And I am thrilled with that too. But it has to do with money! I mean, I feel like I’m preaching to the choir here. But that’s what I think—unless we solve the problem of delivering basic human needs to all the communities, globally, we’ll never get rid of it.

RZ: Well, maybe we can thank Peter and travis very much.

PK: I’m very honored to have been here, thank you.

t: Thank you, thank you, thank you.